YeoJohnsonTransformer#

The YeoJohnsonTransformer() applies the Yeo-Johnson transformation to the numerical variables.

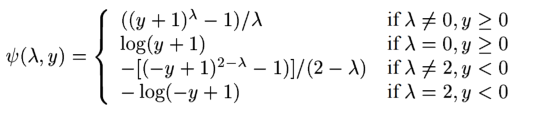

The Yeo-Johnson transformation is defined as:

where Y is the response variable and λ is the transformation parameter.

The Yeo-Johnson transformation implemented by this transformer is that of SciPy.stats.

Example

Let’s load the house prices dataset and separate it into train and test sets (more details about the dataset here).

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from feature_engine import transformation as vt

# Load dataset

data = data = pd.read_csv('houseprice.csv')

# Separate into train and test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

data.drop(['Id', 'SalePrice'], axis=1),

data['SalePrice'], test_size=0.3, random_state=0)

Now we apply the Yeo-Johnson transformation to the 2 indicated variables:

# set up the variable transformer

tf = vt.YeoJohnsonTransformer(variables = ['LotArea', 'GrLivArea'])

# fit the transformer

tf.fit(X_train)

With fit(), the YeoJohnsonTransformer() learns the optimal lambda for the transformation.

Now we can go ahead and trasnform the data:

# transform the data

train_t= tf.transform(X_train)

test_t= tf.transform(X_test)

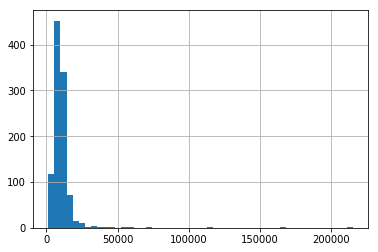

Next, we make a histogram of the original variable distribution:

# un-transformed variable

X_train['LotArea'].hist(bins=50)

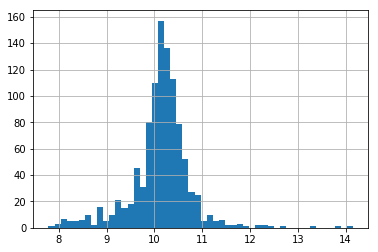

And now, we can explore the distribution of the variable after the transformation:

# transformed variable

train_t['LotArea'].hist(bins=50)

More details#

You can find more details about the YeoJohnsonTransformer() here:

For more details about this and other feature engineering methods check out these resources:

Feature engineering for machine learning, online course.