PowerTransformer#

The PowerTransformer() applies power or exponential transformations to numerical

variables.

Let’s load the house prices dataset and separate it into train and test sets (more details about the dataset here).

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from feature_engine import transformation as vt

# Load dataset

data = data = pd.read_csv('houseprice.csv')

# Separate into train and test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

data.drop(['Id', 'SalePrice'], axis=1),

data['SalePrice'], test_size=0.3, random_state=0)

Now we want to apply the square root to 2 variables in the dataframe:

# set up the variable transformer

tf = vt.PowerTransformer(variables = ['LotArea', 'GrLivArea'], exp=0.5)

# fit the transformer

tf.fit(X_train)

The transformer does not learn any parameters. So we can go ahead and transform the variables:

# transform the data

train_t= tf.transform(X_train)

test_t= tf.transform(X_test)

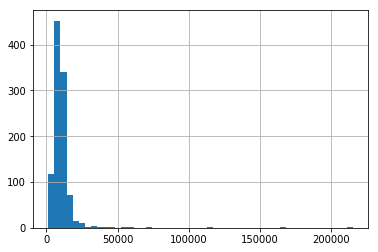

Finally, we can plot the original variable distribution:

# un-transformed variable

X_train['LotArea'].hist(bins=50)

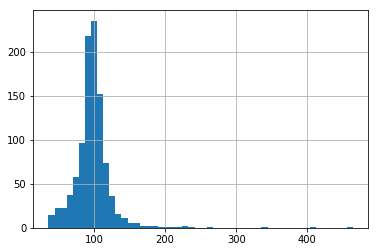

And now the distribution after the transformation:

# transformed variable

train_t['LotArea'].hist(bins=50)

Additional resources#

You can find more details about the PowerTransformer() here:

For more details about this and other feature engineering methods check out these resources:

Feature Engineering for Machine Learning#

Or read our book:

Python Feature Engineering Cookbook#

Both our book and course are suitable for beginners and more advanced data scientists alike. By purchasing them you are supporting Sole, the main developer of Feature-engine.